EVs Explained: Don’t Let the Jargon Fool You

written by Gordon Rodda and Deborah Lycan, and originally posted at EV Four Corners

HEV, PHEV, BEV: They are all EVs, right? Wrong.

The names are confusing, and it can be argued that they are meant to be; there is money to be made in keeping you confused about them. In the last couple of years, the industry has been playing around with new names, in part to beat the regulators, and in part to coax buyers into purchasing whatever happens to be in the dealer’s inventory or is more profitable for the dealer. Twice in the last month, we’ve heard of people who walked into a dealership keen on buying an “EV” only to walk out the new owner of a car that runs entirely on gasoline (“The salesman said it was an EV”).

For the record, there are four classes of vehicles, of which only the latter two are EVs:

The important distinction to be aware of here is that the two kinds of hybrids are not the same thing. Basically, if it can’t be plugged into an electrical outlet, it is not an electric vehicle, regardless of what someone calls it. Only the chargeable hybrid has two fuels: gas and electricity. Unchargeable hybrids are gas cars; the only electricity they use is obtained from regenerative braking on deceleration or downhill runs, both of which were made possible by burning gasoline during uphill runs and acceleration. The only fuel possible in an original Prius or unchargeable RAV4 hybrid is gasoline, which is a fossil fuel that causes climate change, albeit at a slower rate of increase than a less-efficient gas car.

The chargeable hybrids are very popular with many buyers because they cause no range anxiety (gas stations are ubiquitous). A chargeable hybrid car can switch back and forth between fuel types automatically; nothing is required of the driver. Furthermore, the electric range of a chargeable hybrid (8 to 80 miles depending on model) may be sufficient to cover one’s daily driving needs. If it is, most trips can be done without using any fossil fuels. A chargeable hybrid can be recharged overnight from any household outlet; the electric motor is silent, the acceleration breathtaking, and the fuel is cheap.

Be aware of confusion surrounding the word “hybrid”. Some players in the auto industry prefer to lump unchargeable hybrids in with chargeable hybrids for a pool of “hybrids”. Contributing to the confusion, the Prius (and many other unchargeable hybrids) come in both unchargeable and chargeable “builds”. For example, for many years, the Prius could either be a regular Prius or a Prius Plus (now marketed as a Prius Plug-in Hybrid). The Prius Plus was a chargeable hybrid, whereas the Prius was not. As it happens, the profit margin is significantly higher for the unchargeable build than it is on the chargeable build, and many salespersons will steer you in the direction of their fattest profit.

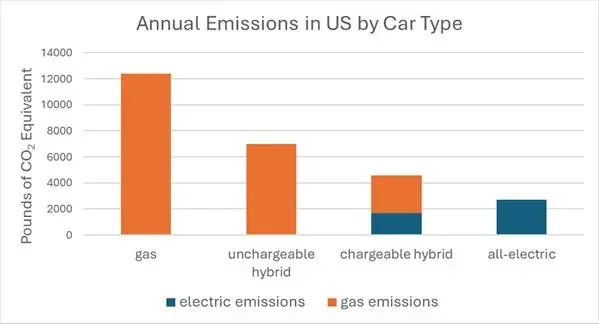

Here are the average per-year life-cycle per-car carbon emissions for the United States by a federal energy data keeper (Alternate Fuels Data Center) using the latest (2022) data and assumptions from the federal Energy Information Administration. In this lifecycle analysis, all tailpipe and car-manufacturing emissions from power plants, chemical releases to the atmosphere, fuel production, fuel burning, etc., that were generated to make and drive the car and its components are totaled and divided by the number of years that the car is expected to remain in use. All gasoline car-attributable emissions are represented in orange columns, whereas electric car-caused emissions (mostly but not entirely from electricity generation) are shown in dark blue. The chargeable hybrid emissions are allocated based on the split of the car’s miles that are driven by the gas engine or the electric motor, respectively.

Some important footnotes:

These are cradle-to-grave (lifecycle) estimates that are strongly dependent on how long a car remains in service (i.e., before it is put in the “grave”). The lifetime mileage assumption built into these numbers (typically 80K miles) is quite conservative for EVs, as EV lifetimes are not yet known for most models. Realized average EV emissions will be lower than shown here if car durability improves upon these assumptions.

Much depends on the fuel mix used to generate your electricity. You can greatly reduce your EV emissions by using clean electricity (e.g., charging during the day in our solar-based area, or drawing from your own rooftop PV electricity). Regardless, EV emissions will go down as the grid gets cleaner.

The height of the bars in this graph is based on the mix of vehicles on US roads. This means that comparing the heights of any two bars not only contrasts the emissions of those types of vehicles but also the choice of models that buyers make. For example, most American buyers favor heavy SUVs and pickup trucks; those are heavily represented in the “gas car” bar but nearly absent from the “unchargeable hybrid” bar. In some cases, you can focus on the propulsion system alone by finding popular models that are made in both versions. The two versions are rarely completely identical except for the propulsion system, but it is the best you can do. For example, comparing the 2023 Ford F-150 pickups, there is both an unchargeable hybrid and a gas car version that is two-wheel drive, with a six-cylinder automatic transmission, etc., of which the EPA combined mileage estimate for the gas version is 21 mpg, and that of the unchargeable hybrid is 25 mpg. In other words, the hybrid uses 84% of the gasoline that the gas version does. This type of comparison is a better reflection of the relative fuel economy of gas compared to unchargeable hybrids. The roughly two-fold difference between the gas car and unchargeable hybrid bars in the graph is due mainly to differences in model choices by buyers of the two types; similar phenomena affect all bars to some degree, though the model choice discrepancy is probably most significant for the first two types.

For the record, maintenance costs are model-specific but are generally highest for the chargeable hybrids (two independent power sources provide more ways for things to go wrong). Gas and unchargeable hybrid cars are the next most costly to maintain. All-electrics are comparatively maintenance-free (As Elon says, we took out 2000 moving parts and replaced them with 12).

Why do you care about the differences in CO2 emissions among vehicle types?

You may not (e.g., you like the rocket-like acceleration of an EV). You may care primarily about the health impacts on people breathing your exhaust (in which case, you should be very attuned to the fuel mix used in your area, as you don’t want to simply swap your exhaust pipe emissions for power plant emissions). Most of our readers also care about greenhouse gas emissions because the livability of Earth is rapidly declining in the face of fossil fuel use.

A critical fact about CO2 emissions is that they are cumulative throughout human history. Although much of the fossil fuel emissions to date have become dissolved in our oceans, that dissolved CO2 will return to the atmosphere once we develop methods to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The natural (geological-speed) sequestration of carbon is too slow to be relevant to policy (in theory, humans could engineer rapid geological sequestration, but no practical method for doing so has been invented). Until a breakthrough in sequestration occurs, our climate will continue to degrade for as long as, and to the extent that, humans are burning fossil fuels. Fossil fuels are not just the centerpiece of climate change; they are the only significant cause of climate change.

Put in the context of the graph above, the differences between the car types are a proxy for the speed with which our personal possessions are accelerating the degradation of the planet. We can help slow the acceleration down, but we will not reverse the degradation caused by transportation until the grid is entirely clean and everyone is driving all-electric EVs or other zero-emission forms of transportation. This is a very tall order. Everyone should be encouraged to reduce their emissions in any way that they can as soon as they can, as many vehicles remain in service for decades. Learning how to charge an all-electric is not a big ask. Transportation is one of the very few climate change modifiers that we personally control. The planetary costs of personal ground transportation are proportional to the height of the bars shown above.

Why are the majors obfuscating the electric vehicle definitions?

The dealerships, in particular, want to sell you a vehicle that enhances their profit margin. They make their money on repairs and selling models that the manufacturer has already developed, not new models with low maintenance needs.

The Inflation Reduction Act under Biden was written to promote electric vehicles, but was unclear as to whether that Act would promote chargeable hybrids. Certain legacy manufacturers wanted to keep milking their investments in chargeable hybrids, so they lobbied the Biden Administration to halve the number of EVs that needed to be sold by conflating the chargeable hybrid and all-electric categories.

RAM came late to the EV pickup truck game and wants its chargeable hybrid truck, the Ramcharger, to be considered a peer among the E-pickups. But the other trucks, like the Rivian, the F-150, and the Tesla Cybertruck, are all fully electric EVs. The RAM advertisements don’t actually acknowledge that their vehicle is a chargeable hybrid, not a fully electric truck. (and as of July 2025, still don’t use the word “hybrid”).

Toyota and Subaru have been touting their gas cars as PZEVs (notice those letters on the rear right of many of their cars), which stands for Partial Zero Emission Vehicles. In fact, they are regular gas cars (which happen to be compliant with a smog rule in California). They are not zero-emission vehicles (= all-electrics or fuel cells). They are not even partially electric or fuel cell vehicles. Toyota and Subaru appear to simply want to burnish the green image of those models by tossing out an unfamiliar acronym that sounds good.

A recent New York Times article on “hybrids” followed the Toyota press release by pooling sales of unchargeable hybrids with chargeable hybrids. They cited the significant upswing in sales of “hybrids” without breaking out which were chargeable and which were not, to justify a slowdown in all-electric model development.

Knowing the Difference Between EV Types Matters

When it comes to electric vehicles, names matter—and so does knowing what you’re actually driving off the lot. As carmakers and dealerships blur the lines between hybrids and fully electric vehicles, it’s up to consumers to stay informed. Don’t let the industry’s alphabet soup steer you wrong—ask questions, read the fine print, and make sure your EV is truly electric.